Having looked at Anacamptis, Orchis and Dactylorhiza genera in my previous blog (The most beautiful monocot?) it’s time to look at Ophrys, the bee, spider and fly orchids, which I’m hoping to see next week in Cyprus. From a botanical point of view, they differ from Orchis and Dactylorhiza species in having the rostellum (the pouch enclosing the anthers) divided in two.

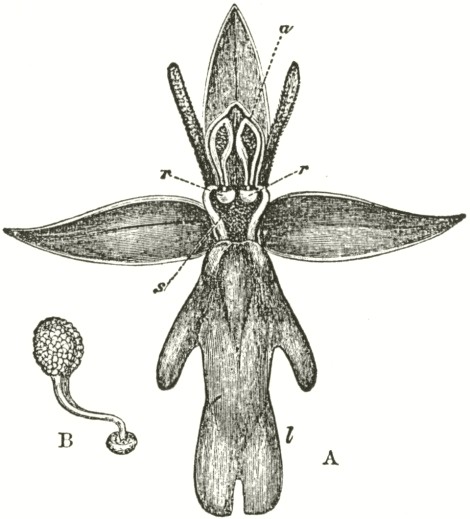

Ophrys muscifera (Fly orchid) from Darwin’s, ‘On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing’ a. anther; r. rostellum; s. stigma; l. labellum.

A more obvious distinguishing feature, however, is the furry labellum. Our only British bee orchids (O. apifera) are not uncommon around here, growing happily in several of the old limestone quarries in Co. Durham.

Ophrys apifera, Co. Durham – top right photo shows dangling pollinia

The flowers have something essentially duck-like about them, to me, but are named for the distinctive labellum designed to help attract solitary bees, which pick up pollen whilst attempting to mate with the flower. Britain, however, is at the northerly end of their range, and here the flowers mostly self-pollinate. Darwin observes that the stalks or caudicles holding the pollinia are remarkably long and flexible in O. apifera and gradually drop until they contact the stigma (see the middle photo, above). Self pollination greatly improves the reliability of seed set but this must be traded off against a reduction in the amount of new genetic material introduced by outcrossing. The balance obviously shifts across the plant’s range as it wouldn’t normally be worth investing the resources necessary to produce such a sophisticated flower just for it to self-pollinate.

Several of the other Ophrys I’ve seen have been in Crete and Malta and are not found in the UK so it’s a bit of a cheat to include them here. Ophrys lutea is by far the most distinctive, with its yellow-edged labellum. It’s also distinguished by the fact that the solitary mining bees which pollinate it sit on the labellum facing away from the pollinia, so collect pollen on their abdomen rather than on their head. I’m sure there is a joke in there somewhere!

Bee orchids, Crete. Top left; Ophrys cretica, right; Ophrys fusca. Bottom, Ophrys lutea.

I’ve also seen spider orchids in Crete though, if I lived on the south coast of England, I might have seen these species here, though they are rare and declining in number. The Early spider orchid, at least, does look a little more like its namesake.

Left; Early spider orchid, Ophrys sphegodes. Right; Late spider orchid, Ophrys fuciflora, Crete

The Early spider orchid, unlike the Bee orchid in Britain, does depend on a bee for pollination – a male solitary mining bee, Andrena nigroaenea, to be specific. In last Friday’s Guardian newspaper, Patrick Parkham highlighted research by Michael Hutchings and colleagues at Sussex university which shows that climate change is causing great problems for these orchids. Historically, there is a time lag between the male and female bees emerging from winter hibernation and the orchids capitalise on this. The flowers produce chemical scents mimicking that of a virgin female bee so that early-emerging male bees will try and mate with the flower, picking up and transferring pollen along the way. This works fine, as long as there are no real female bees about. It has always been a slightly unreliable strategy but, as our springs get warmer (hard to believe this year, I know) the female bees are often emerging before the orchids start to flower so the orchids are ignored and flowers remain unpollinated. This has happened in 26 years out of the 28 years up to 2014, meaning that little, if any, seed was set during those years – it’s not hard to see why the orchid is declining.

My last Ophrys is another Mediterranean species, going by the wonderful common name of the Woodcock orchid. I’m not entirely sure I can see the resemblance to the bird after which it is named though!

Woodcock orchid, Ophrys scolopax, Crete (left) and Eurasian woodcock, Scolopax rusticola (right). Image; Ronald Slabke via Wikimedia commons

I’m hoping to find more Mediterranean Ophrys on Cyprus next week – watch this space. Looking at this lovely blog, the chances seem good!

Hutchings M.J. et al. (2018). Vulnerability of a specialized pollination mechanism to climate change revealed by a 356-year analysis. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 186, pp 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/box086

[…] provides a landing platform for insect pollinators. The same quarry sites locally where I’ve seen bee orchids host large populations of Dark-red helleborine, Epipactis atrorubens, the only helleborine I’ve […]

[…] The most exciting find of my first foray out was a couple of bee orchid spikes with pure white sepals amidst a damp meadow full of pyramidal orchids, Anacamptis pyramidalis. Presumably the bee orchids do well with plenty of bees to trick into pollinating them! […]

[…] by councils using artificial seed mixes . There are many more Fragrant orchids too and a few Bee orchids in a patch of shorter grass at the top and one of my favourite, tiny flowers – Fairy flax, Linum […]

[…] a drab brownish colour. On closer inspection the flowers are as intriguing and deceptive as their Bee orchid relatives. The flower lip is a deep, velvety brown with a brighter, bluish patch known as a speculum across […]