I’ve just returned from a thoroughly-enjoyable, week-long Ecology field trip with Durham Bioscience undergraduates at the end of their first year of study. The students get the bulk of their teaching for this second year module on site in Arnside and Silverdale AONB, then carry on learning with a series of student-led seminars during their second year. The beauty of the field week is the way the students are exposed to a wide range of field techniques and taxa, often finding out that they are interested in groups of organisms they’d never really thought about before. Daytime activities involve learning how to ID plants and survey for diversity in a range of habitats, how to identify wetland birds and assess the number of species present using MacKinnon listing, looking at how niches are partitioned amongst woodland birds by observing their behaviour and at how the size distribution of woodland trees can reveal information about population structure.

Students also get to learn about identifying birds by their songs and about using sweep nets to sample invertebrates in the herbaceous plant layer. Each evening they get to set up either light traps for moths, Longworth traps for small mammals or camera traps for larger mammals – a real cornucopia of methods and taxa with, crucially, a frequently repeated mantra about why all this biodiversity matters.

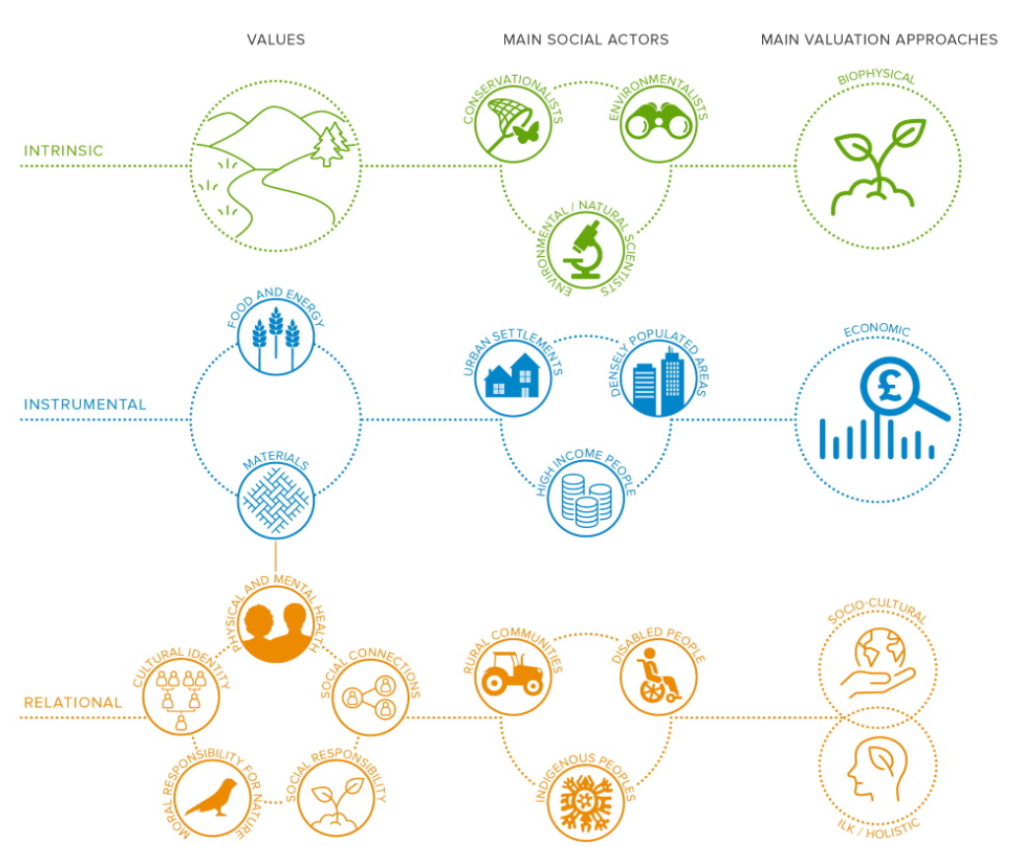

Mostly we were looking at Biodiversity from an ecologist’s point of view, thinking about its importance in maintaining healthy ecosystems, with as much resilience as possible in the face of looming climate change. Many of the techniques taught to students aimed to measure biodiversity using metrics such as species richness and relative abundance, or ecosystem productivity – all of key importance to conservationists. However in an article for the Royal Society, Berta Martín-López points out that nature can be valued in multiple different ways; it has intrinsic value, deserving moral consideration in its own right, but it also has instrumental value as a means to meeting human needs (sometimes given monetary value as ‘Ecosystem services’) and relational value as a result of the meaningful relationships between nature and people and amongst people in a natural environment. Martín-López’s figure (below) shows how different groups of people (social actors) are more likely to perceive and attempt to evaluate nature’s value in particular ways.

Of course the three types of values interact, sometimes synergistically, with one another. Martín-López cites the example of how someone going into a forest to pick mushrooms (using its instrumental value) can, over time, start to build a meaningful relationship with the forest (giving it relational value) and perhaps perceive it as having intrinsic value too.

In order to fully understand how nature matters to people you need to have ways of evaluating all these aspects. Historically, conservationists have mostly been interested in the intrinsic value of the natural world and have assessed this using the kind of quantitative methods we were teaching students. In the early part of the 21st century, the balance shifted towards the instrumental value of biodiversity – what it does for us – and attempts were made to estimate the monetary value of nature and to use these values in a kind of cost-benefit analysis to justify conservation work. Relational values are much harder to quantify and need to be assessed by a different approach, making used of qualitative social-science techniques such as interviews and participant observation.

Martín-López argues that trying to assess the multiple values of nature is about justice as much as about biodiversity because it is the only way in which the voices of different groups can be heard – those individuals who may lose out in the short term when conservation action is taken, as well as those in positions of power who drive change. The unhappiness of some stake holders (largely farmers) about the recent creation of a SSSI on West Penwith Moors and Downs in Cornwall suggests we have some way to go to achieve a situation in which individuals feel their needs are balanced fairly against the wider common good. Natural England designated the area an SSSI because of its diverse assemblage of rare habitats (lowland heathland, fens, dry acid grassland and wetland valley mires) and also for some of the rare species it supports; lichens, breeding Dartford warblers, invertebrates and vascular plants, such as Coral-necklace (Illecebrum verticilatum), a tiny member of the Campion family which grows along damp tracks.

Photo C T Johansson, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Although Natural England say they are committed to continuing “to support and reward the nature-friendly farming that is essential to sustain West Penwith Moors and Downs” by helping farmers apply for Countryside Stewardship money, many farmers are worried by the uncertainty around restrictions they will face and changes they will have to make to their farming practice. Although I’m not sure British farmers are really the marginalised voices Martín-López is talking about, some may feel they are. Everyone – conservationists, farmers and the general public alike – need to think about the value of nature in the broadest possible way and perhaps our undergraduate teaching needs to change to accommodate this. After all, as Tony Juniper says, “Nature provides us with clean air, food, water and other essential resources. It regulates our climate and is fundamental to our health and well-being. Nature is at the heart of every successful sustainable economy.” We ignore it at our peril.

Martín-López, B. Plural valuation of nature matters for environmental sustainability and justice | Royal Society

[…] browsing the second hand books for sale at Leighton Moss RSPB reserve on our recent field trip I was intrigued enough to part with a little cash in exchange for a book titled, ‘On Buds and […]