Our third destination in Tunisia was Kairouan, allegedly Islam’s fourth holiest city and site of the oldest mosque in Africa. The drive north and west here from Chebba took us through miles and miles of olive plantations, much like we’d seen along the coast. Mostly the olive trees are widely spaced and sometimes the ground under them seems to have been deliberately cleared, which makes me wonder whether something which was growing beneath the trees has already been harvested. I suspect the landscape looks completely different in the spring. Some kind of agroforestry making use of the shade cast by the trees to reduce water stress on annual crops would seem a no-brainer in such a hot, dry climate. There is growing evidence that it is an efficient way of using land, even if the arable crop yield is a little lower because of the reduced light availability (Temani et al., 2021). As we approached Kairouan, there was more evidence of cereal crops having been recently harvested, with stubble in the fields and lorries teetering towards us, piled high with bales of hay.

In complete contrast to what I’d expected, given its holy status in Islam, Kairouan feels a very relaxed city, with more casually dressed youngsters than women in niqabs. We spent both our evenings there ambling around the medina amongst crowds of Tunisian families, enjoying their weekend. I can’t imagine being comfortable in such night-time crowds in many places! All the usual sources of pester power for children were in evidence, particularly on Sunday evening when the prophet Mohammed’s birthday was being celebrated – balloons, toys with flashing lights, and trays of pastries and brightly coloured sweets. The bag scanners put in place for the evening on the entrances to the mosque were manned by local Scouts, somehow making it seem like a family affair.

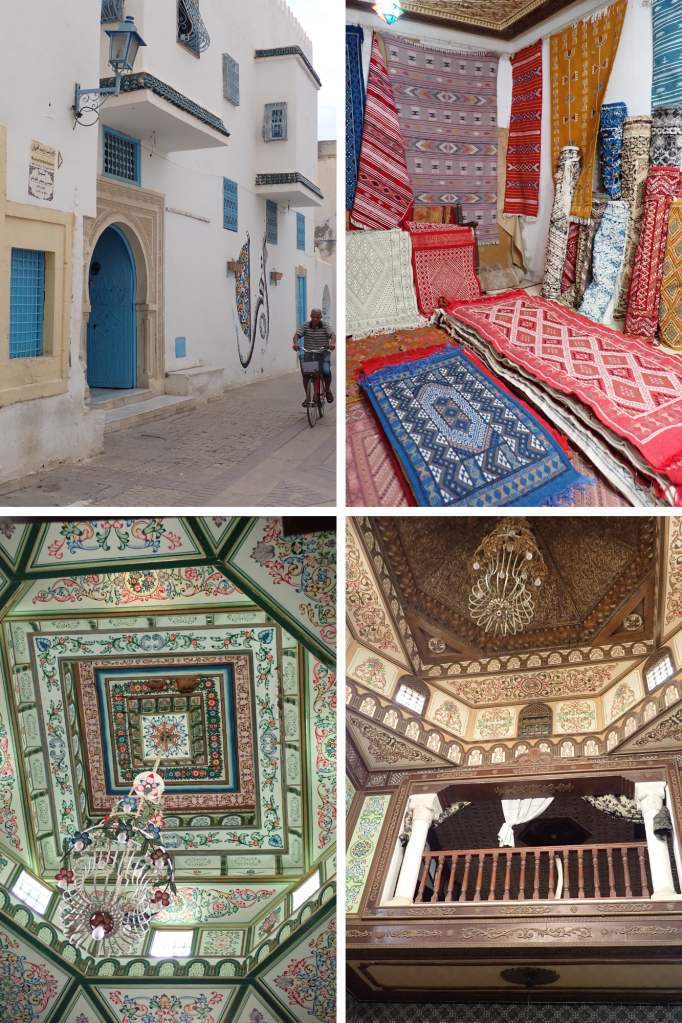

The walls around the medina here are on a much bigger scale and more complete than we’ve seen so far in Tunisia, reminding us very much of Kano, in northern Nigeria. In the heat of the day, the high buildings and narrow lanes of the medina remain pleasantly cool and we spent a lot of time ambling through the backstreets, as well as visiting the sights.

We were in need of a new pestle and mortar and some small dishes for serving mezze, which gave us a little reason for shopping along with the locals, in the souk. Although plenty of tourist buses come here for the day, most don’t seem to stay long enough to explore the backstreets.

Our one visit to a carpet selling emporium was very low pressure and, as this was housed in the 18th Century Governor’s house, gave us some insight into what lies behind some of the more ornate household doorways in the medina. Most are, presumably, not quite so grand inside! This one, residence of the former beys of Kairouan, has 17 rooms on the ground floor alone, not counting the upper rooms where his harem would have lived. Each room is more sumptuous than the last, panelled with intricately-carved hardwood, latticework and tiles – quite overpowering in its effect!

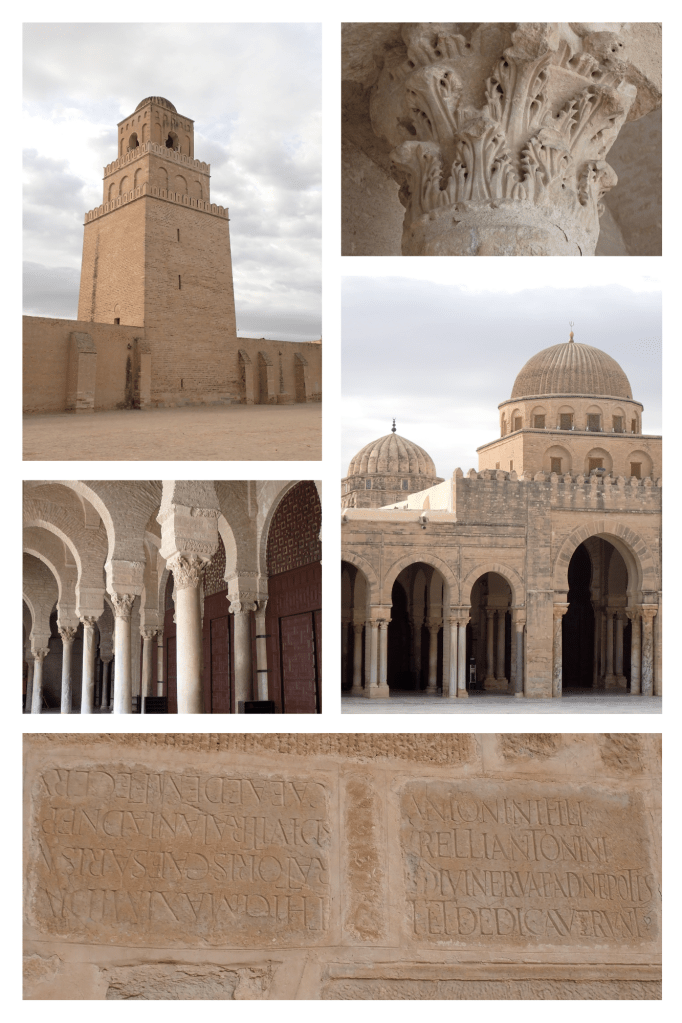

Of course we visited the Great Mosque built, in this austere incarnation, by the Aghlabid dynasty in the 9th Century. The original, built by the founder of Kairouan general Uqba ibn Nafi in 670 AD, was destroyed only 20 or so years later by Berbers. Non-Muslims are welcome in the main courtyard and the beautifully carved doors into the prayer hall are left open so you can peek in. Just like those who lived along the route of Hadrian’s wall, in NE England, people here shamelessly recycled stone from earlier Roman buildings, sometimes more cleverly than others, if you look at the bottom blocks of stone in the picture!

On Saturday afternoon we walked out past the mosque to the Aghlabid basins, cisterns built around the same time as the Aghlabids rebuilt the mosque, to hold water brought into the city by aqueduct from the foothills of the Atlas mountains, more than 30 km away – quite a feat of engineering. The main pond is 128 m across and 5 m deep so can store vast quantities of water but I wouldn’t fancy drinking or even washing in the water they hold today. A lack of water at this time of year is one problem but there is also a chronic problem with litter, particularly plastic, here; Africa News cite a figure of 6.8 kilos of plastic discarded daily per kilometre of Tunisia’s 1300 km coastline and don’t mention the plastic bottles and bags we also see blowing around away from the coast. An informal network of barbechas are responsible for some recycling but a lack of garbage trucks and money to pay for services limits what they can do.

There was some kind of women’s festival happening, though, so there were plenty of opportunities for people-watching and Martyn, for once, was the one feeling outnumbered!

The culinary highlight of Kairouan was our meal at El Brija, in the shadow of the Great Mosque, for many reasons; we had hunted long and hard for something to eat that wasn’t a sandwich, I had managed to ask for and follow (admittedly very simple) directions in Arabic to find it, the atmosphere was great and I got to eat very tasty couscous and fish!

I’m currently reading The Secret River, by Kate Grenville, which tells the story of a transported convict and his family making a new life for themselves in Australia, alongside Patricia Highsmith’s The Tremor of Forgery, set in Tunisia. It must be holiday time! Both are morality tales of a sort, set in very different times, but with protagonists whose flaws make them more sympathetic characters than perhaps they deserve.

Temani F., Bouaziz, A., Daoui K., Wery J. & Barkaoui K. (2021). Olive agroforestry can improve land productivity even under low water availability in the South Mediterranean. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 307, 107234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107234.