Our route from Le Kef to our final holiday destination here, at Sidi Bou Said, took us past the ancient Roman (and pre-Roman) city of Dougga, so it would have been rude not to stop! If we were impressed by Makthar, this was on a whole different level. Its UNESCO World Heritage Site citation says that Dougga represents, “the best-preserved Roman small town in North Africa”. The Roman city was built on the site of an older Numidian (Berber) settlement, Thugga, on a hillside with natural springs, overlooking the Kalled valley. There are the show-stopper remains, of course; the 3500 seater amphitheatre, the Capitole, temples to several important Roman gods and a large bathhouse but what really struck us was the sense of being in a city full of narrow streets and houses, rather like a modern day medina.

Theatre and the Square of the Winds

A remarkable proportion of the walls of houses in the city remain intact. These are now known to be from the 3rd to 7th Centuries AD, so built by either the later Romans or the Byzantines, who, remodelled the site as a fort in 533 AD. Most of the big Roman buildings were built by wealthy citizens during the second and third Centuries AD, when Dougga was home to around 5000 people.

Apparently people were still living in the ruins until the early 1950s and, exploring the north west part of the site, we certainly found rooms with intact roofs which would have provided good shelter for families such as the shepherds whose flocks still graze the area today.

The most embarrassing bit of history here, from the point of view of a Brit, concerns the 2nd Century BC Libyco-Punic mausoleum towards the bottom of the site; one of the Tunisia’s finest pre-Roman monuments, or at least it was until Thomas Reade, the British Consul in Tunis, got his hands on it. Uniquely, the inscription which decorated one face of the obelisk is written in both Libyan and Punic script so, in 1842, Reade had the inscription removed in the name of being able to decipher the Numidian (Libyan) alphabet, and had it sent to the British Museum (of course) where it still is today.

Not content with ripping out the inscription, Reade demolished the entire wall in which it was embedded in the process. Fortunately, his colleagues made some sketches of the mausoleum before it was damaged and it has now been partly restored. Translated, the inscription reads:

“Here is the tomb of Atban, son of Iepmatah, son of Palu: the stoneworkers were Aborsh son of Abdashtart Mengy son of Oursken, Zamar son of Atban son of Iepmatah son of Palu, and among the members of his house were Zezy, Temen and Oursken; the carpenters were Mesdel son of Nenpsen and Anken son of Ashy; the metalworkers were Shepet son of Bilel and Pepy son of Beby.”

However, it now seems that these were the people who built the mausoleum, rather than the people to whom it was dedicated. A second, long-missing inscription may have been to Massinissa, the Numidian prince who led the Berbers during the second Punic War between Carthage and Rome.

As we’ve headed north and east towards Tunis the landscape has visibly greened, with fresh vegetation already sprouting where wheat has been harvested. I wasn’t expecting that in the interior of Tunisia, but it has meant our wanders around Roman sites have had some botanical interest too. Dougga may have an average of only 58 mm of rain a year, but that’s a whole 10 mm year more than El Kef and its annual mean temperature is also around 0.5 °C lower.

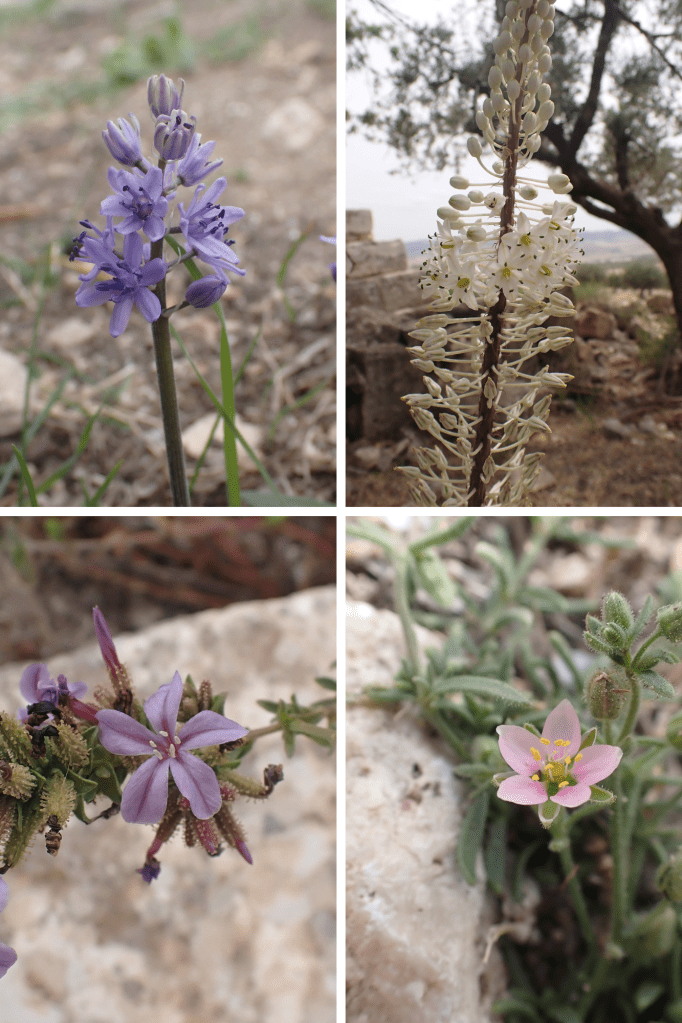

My favourite finds in flower at Douga were two members of the Asparagus family – tiny blue Autumn Squill and statuesque white Sea Squill, which also grows happily inland. Sea Squill, Drimia maritima, has been used medicinally in the past as it is full of toxic cardiac glycosides, similar to those found in Foxgloves at home, but getting the concentration right is tricky and the powdered bulbs are more often used as rat poison today. It’s an unusual plant in that it produces leaves from a bulb during the spring, which then die back almost completely before the flowering spike is produced in the autumn. Fortunately for the sheep and goats grazing around Dougga, the leaves lose their toxicity as they dry out Growing from bulbs like this is often a safer bet for plants than depending on seeds when the climate is hot and dry for long periods of the year. Many of the other plants here are also adapted to drought conditions – with Sand-spurrey, the clue is in the name and Plumbago is in the same family as the Sea Thrift which grows on the coast in the UK.

Drimia maritima; Sand-spurrey, Spergularia rubra; Plumbago europaea

It’s been good to get back to my normal routine of looking out for three good things in nature and an added pleasure to get a good look at a Redstart on a wall above the amphitheatre, passing through from its breeding site in Europe to winter grounds in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Redstart’s scientific name, Phoenicurus phoenicurus, seems particularly appropriate when our next historic site will be the Phoenician city of Carthage!

I’ve just finished reading The Secret River by Kate Grenville and had to skim quickly over the section dealing with the genocide of aboriginal Australians by British settlers of the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney, as it was too distressing to read. A fascinating book, and very honest about what went on, but not one I could say I’ve enjoyed.

The culinary highlight of our drive to Tunis (yes, there was one) was a freshly baked chapati stuffed with salad, egg and tuna from a roadside stall – delicious.

This is all very interesting Heather. You Botanised at last.😊

Thanks for sharing.

Gladys

Sent from Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg

It’s a fascinating place, Gladys x

[…] Dougga I’m afraid the ruins of Carthage are a little underwhelming, though Byrsa Hill offers amazing […]

Yes after the Brit consul trashed it, what you see today is in effect at least in part a reconstruction thanks to the efforts of Louis Poinssot. James Bruce (1730 – 1794), the Scottish travel writer, undertook a sketch of the site in the eighteenth century prior to its partial destruction.